As Eastertime has once again, what better than to dive into a classic cookbook, Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management. The supermarkets have been full of hot cross buns of all flavours over the last few months. There are the traditional fruited buns but also lemon curd, raspberry, white chocolate, orange, salted caramel, apple and cinnamon, and one of my personal favourites this year, chocolate. These are far from the traditional hot cross bun. So let’s join Mrs Beeton and explore a more traditional recipe. The recipe I am using is from the 1869 edition of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management. It is familiar but slightly different to more modern recipes. First lets consider how this very English Easter tradition got started. Mrs Beeton’s recipe is below if you want to try if yourself or you can watch the short video. First let’s explore the history of hot cross buns.

Traditionally hot cross buns were eaten on Good Friday (the Friday before Easter Sunday). Historians debate over the origins but the name ‘hot cross bun’ or ‘cross bun’ is not used until the 18th century. Newspaper articles from the 19th century also debated the origins of this bun suggesting it dates from Greek and Roman times. Some still maintain that the origins of putting crosses onto bread started with the ancient Greeks. Food historian, Emma Kay, suggests that the origins of hot cross buns come from the Roman and Anglo-Saxon deity, Eostre / Eastre, a goddess of dawn, spring and fertility, who was worshipped in April. This festival was adopted by the early Christian church and worshippers continued the custom of offering small cakes. Eventually these took the form of buns marked with a cross. Emma Kay states that cutting a cross into the dough was to ensure any evil spirits would be released and was also used as a protection from enchantment.

“The ‘hot-cross-bun’ is the most popular symbol of the Roman catholic religion in England that the Reformation has left” (Devon and Exeter Gazette, 18 April 1840)

Several 19th century newspaper articles refer to the hot cross bun as a Catholic tradition. Prior to the Reformation, at Easter bread was shared out on Easter Sunday as part of the ritual, but this ritual was swept away with the Reformation. However in rural communities, into the 19th century, superstitions remained, with hot cross buns being kept in homes as symbols of good luck to prevent sickness and disease, and guard against fire or lightening.1

An 1850 edition of The Lancaster Gazette stated that on Good Friday,

“In London, as well as in almost every other considerable town in England, the first sound heard on the morning of Good Friday is the cry of “Hot Cross Buns!” uttered by great numbers of people of a humble order, who parade the streets with baskets containing a plentiful stock of the article, wrapped up in flannel and linen to keep it warm…Hucksters of all kinds and many persons who attempt no traffic at any other time, enter into the business of supplying buns on Good Friday morning”. (The Lancaster Gazette 23 March 1850)

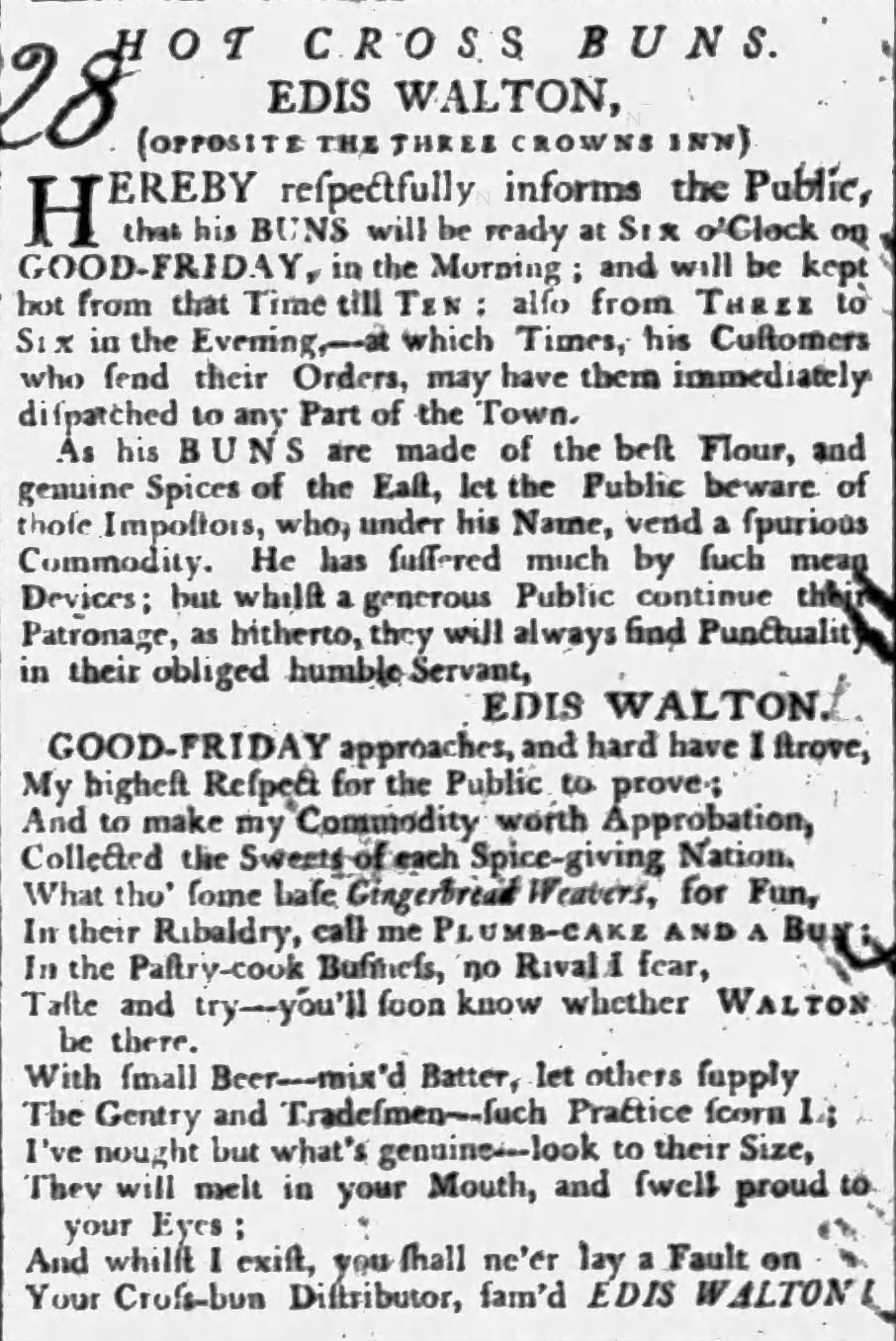

Selling the buns was good business for bakers, street vendors and opportunistic sellers. I found several advertisements details the quality of buns and that they would be ready from 6am. Hot cross buns were originally eaten in a morning as a breakfast food. Edis Walton of Leicester actually seems to have had 2 baking batches one in the morning and one in the afternoon, offering delivery across the town as well. It seems that sellers of fakes have been around for many hundreds of years, as he warns customers against buying from others who may be selling buns using his name. It even includes a rhyme or poem at the end of the advert.

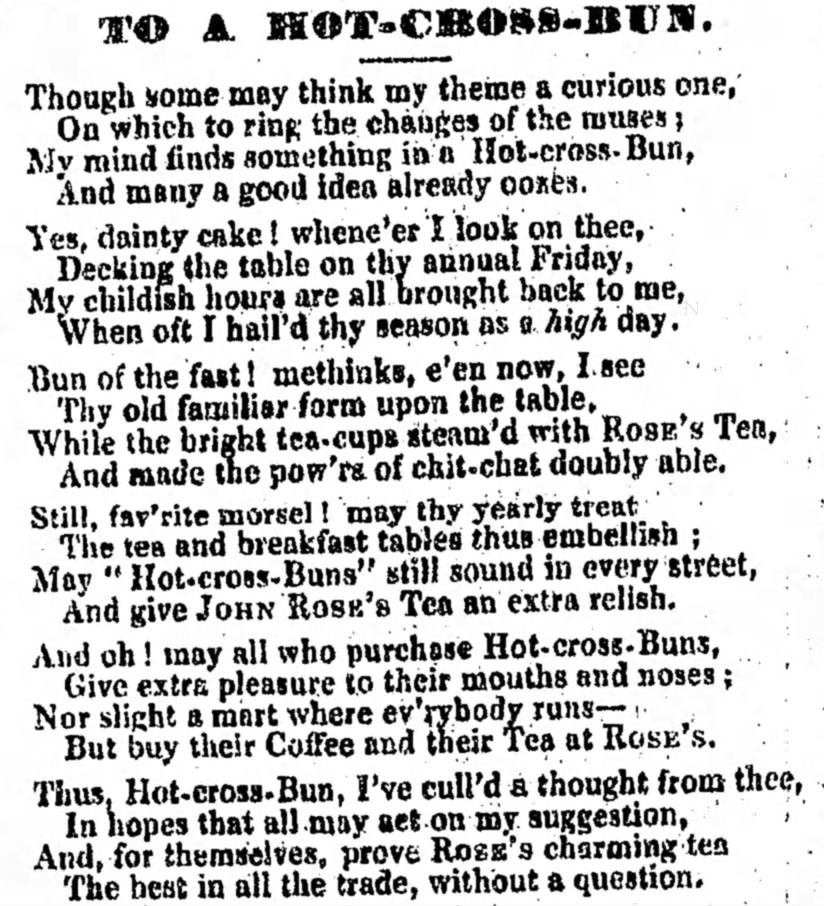

I found another newpaper advertisement in the form of a poem from 1848 about hot cross buns, which is actually advertising Rose’s Tea.

The author of the 1850 Lancaster Gazette article talks about how

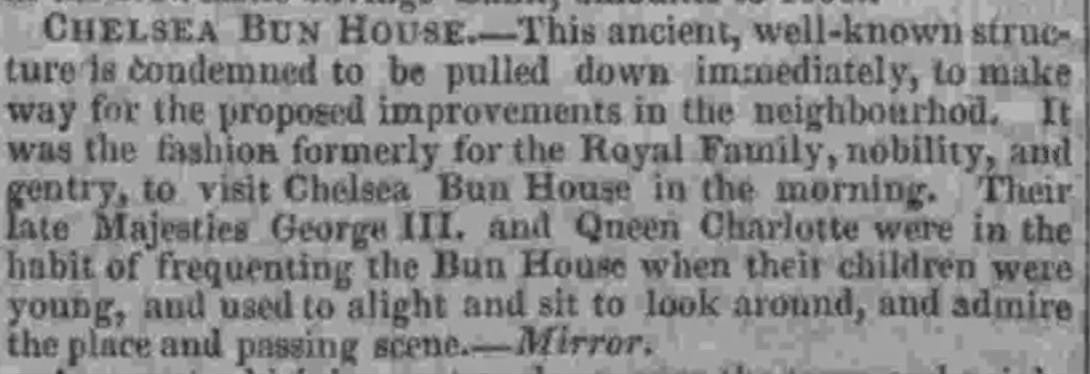

“About a century ago there was a baker’s shop in Chelsea, so famous for its manufacture of excellent buns that crowds of waiting customers clustered under its porch during a great part of the day. The buns were brought up from the oven on small black tin trays, and so given out to the people. The king himself had stopped at the door to purchase hot cross buns, and hence the shop took the name of the Royal Bun-House.” (The Lancaster Gazette 23 March 1850)

A rival ‘Bun-House’ soon appears and the first had to advertise as the Old Original Royal Bun-House. The rivalry had ended by 1850 as it states neither bakery are ‘distinguished’ above other’s in Chelsea. A search amongst eighteenth century newspapers unearthed references in The Observer to properties opposite the Bun-House, Chelsea in 1796 and 1799.

The Chelsea Bun House is actually accredited as originally inventing the Chelsea bun. The bakery is thought to have have originated in the early 1700s being run by the same family for over 100 years. It gained royal patronage but by 1839 it was sold and demolished.2

As already mentioned there was a well known cry of vendors selling hot cross buns which transformed into a nursery rhyme. Apart from the well known 2 lines, there appears to be several versions of this rhyme. Here is one from a 1767 edition of The Leeds Intelligencer.

One a penny, two a penny, hot Cross-buns;

If you’ve no daughters, give them to your sons;

And if you’ve no kind of pretty little elves;

Why then good faith, e’en eat them all yourselves.

Hot cross buns reached their height of popularity in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. A writer in the Devon and Exeter Gazette of 1840 states that the demand for and quality of hot cross buns had declined from some 30 or 40 years previous. Of course recipes remained a traditional Easter food and recipes have continued to appear until the present day.

As an interesting aside the term bun in England has historically referred to a bread made with an enriched dough, rather than just a plain bread bun or bread rolls. Other examples include the above mentioned Chelsea Buns. Bath Buns and Sally Lunn Buns. In Mrs Beeton’s book all the recipes called buns, including plain buns, baths buns, madeira buns and victoria buns are in some way made with an enriched dough. Mrs Beeton’s hot cross bun recipe is enriched with butter and milk but other of her bun recipes are enriched with eggs.

Mrs Beeton’s Recipe for Hot Cross Buns

Ingredients. - 2 lbs of flour, 1/2 lb of sugar, 1 wineglassful of yeast, 1/2 pint of warmed milk, 1/2 lb of butter, 1 lb of currents, 1/2 teaspoonful of salt, 1 teaspoonful of mixed spice.

Mode. - Mix the flour and sugar, spice and currants ; make a hole in the middle of the flour, and put in a glassful of thick yeast and half a pint of warmed milk ; make a thin batter of the surrounding flour and milk, and set the pan covered before the fire till the leaven begins to ferment. Put to the mass half a pound of melted butter and enough milk to make a soft paste of all the flour; cover this with a dust of flour, and let it once more rise for half an hour. Shape the dough into buns and lay them apart on buttered tin plates, in rows, to rise for half an hour. Press a cross mould on them (this may be done roughly with the back of a knife.) and bake in a quick over from 15 to 20 minutes.

Time. - 15 to 20 minutes to bake. Average Cost, 1d. each.

Sufficient to make a dozen buns.

Seasonable on Good Friday.

I made half the quantity of this recipe and found it made 7 large buns. Out of personal preference I used sultanas instead of currants. However currants would have been a cheaper alternative to sultanas or raisins at the time this recipe was written. The recipe would also have used brewers yeast but for convenience it worked perfectly well using dried active yeast instead.

When making this recipes I also noticed the ‘mode’ does not say when to add the salt and I didn’t realise this until I had mixed the other ingredients in. I added it towards the end before the first prove, however this may have affected the rise. The salt should really have been mixed in with the flour and other ingredients at the beginning so it did not directly come into contact with the yeast.

The recipe also does not mention kneading the dough, which I did once it was all combined. It was interesting that it states to add the yeast mix it in a bit and them let it rise. I have not done this before but followed the instructions, left it for about 10 minutes and it did start to ferment. For the first proving it says leave it for half an hour, I found this wasn’t long enough and it probably should have been left at least an hour. However for this experiment I followed the original instructions. The same with the second proving that could have been longer as well.

When shaping the buns it is best to pull the sides up and in several times trying not to get currants on top as they will get burnt, as I found out! Some of my buns did get a bit crispy. I did do a milk wash on them, which the recipe does not state, just to give them a nicer finish.

The end result was some very tasty hot cross buns not a sweet as more modern recipes, they are not glazed like many recipes. Although the cross is not piped it is still effective. The buns having a longer prove would have also given a lighter bun as these were slightly dense and crumbly. I must say I do prefer a slightly more modern (early 20th century) recipe that I have tried before which used eggs in the recipe, piped the cross on the buns and had a final glaze. This recipe gave a lighter and more familiar result.

Hot cross buns are now on sale in supermarkets all year round and I do think they are a delicious bun to make at any time of year. If you want to have a go watch the video.

See Kay, (2020) A History of British Baking. From Blood Bread to Bake-Off. p26-31.

For more information on this see the article entitled ‘The Original Chelsea Bun House’ on All Things Georgian. (https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2022/04/11/the-original-chelsea-bun-house/)

Share this post